GitHub Actions & Security: Best practices - Forking Action repositories

I’ve been diving into the security aspects of using GitHub Actions and wanted to share some best practices in one place. If you want to have an overview how and why you need this, you check checkout a session I have on this topic from a user group recording here.

From the beginning, GitHub always indicated that the best way to use GitHub Actions is to fork the repository containing them and take control over the code that you are running. That way you can review what the Action is doing before you start using it. You don’t want to run just any random code from the internet, would you?

This post is part of a series on best practices for using GitHub Actions in a secure way. You can find the other posts here:

Photo by Anita Jankovic on Unsplash

Always fork the Actions repository and use that!

These days, most GitHub Actions demos only show you how to use them, straight from the source repository. That is scary as heck! We should always mention the best practice of forking them!

Contents

This post will go over the following ways to add more security when you are using GitHub Actions:

- Why should you verify the code the Action is executing?

- Pinning versions

- Forking repositories

- Keeping your forks up to date

Why should you verify the code the Action is executing?

The power of GitHub Actions is that anyone can create a GitHub Action in a public repository for others to use. That also means that there is no real trust between the user that wants to include the Action in their workflow and the maintainer of the Action repository. In the past, there are numerous examples of bad actors taking over respected repositories and changing the code to do something malicious.

That also means the onus of checking what the Action’s code is doing is up to you. GitHub has some methods of limiting the Actions you or your organization can use, but these have some issues as well. Read more on this below. GitHub’s security guidance for Actions can be found here

You can also look at the maintainer of the Action and how many stars, forks and issues the Action has to gauge if the Action is widely used and regularly maintained.

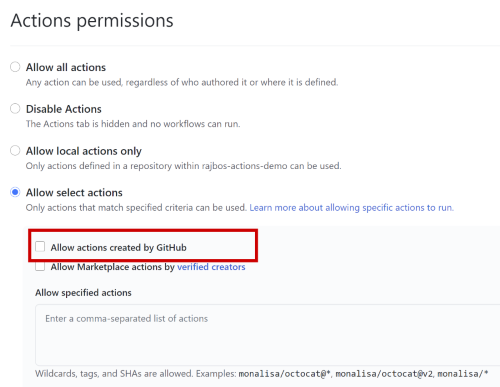

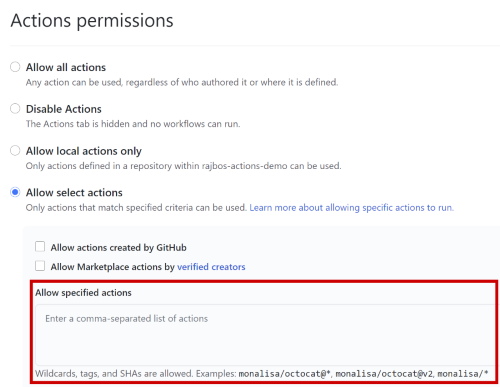

Only allow Actions from GitHub

Your first option to limit Actions being used is to use the setting to only allow Actions made by GitHub. That means that you put your trust into GitHub that the maintainers of the Actions repositories have setup sufficient repository security (limiting who can make changes to the Actions) and always verify incoming changes before publishing new versions of the Actions.

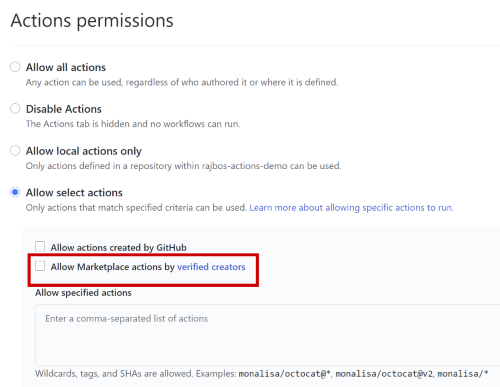

Only allow Actions from Verified Creators

The second option is to limit Actions from verified creators. Unfortunately there is no process (that I could find) to become a verified creator. GitHub only states that the maintainer is a partner that GitHub has worked closely with.

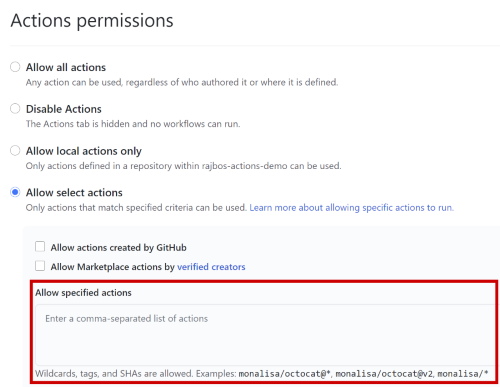

Only allow specific Actions

The third option you have is to limit Actions to the specific ones you list, either directly with the full path to the Action repository, of by using a minimatch filter that limits the Actions to a specific organization.

Note that you can also use specific commit SHA’s here as well, more on that later

Pinning versions

After you have checked the Action itself, you can make the decision to start using them. One of the first options you have is to pin the Action version. By adding the minor or major version of the Action. This will make sure you are always using the same version and (hopefully) prevent any breaking changes from messing up your use of the Action later on.

Example pinning the version

uses: gaurav-nelson/github-Action-markdown-link-check@v1

uses: gaurav-nelson/github-Action-markdown-link-check@v1.0.1

In the example, I’m pinning the major version in the first line to v1 and pinning the minor version to v1.0.1. This works as long as the Action author is using semantic versioning.

The downside of this method is that there is no way to guarantee that the source code of that version has been altered after you pin the version: an author can create a new release (with new code) and use the same version tag for the release. That means that the code that is running in your pipeline could have been altered, without you knowing about it!

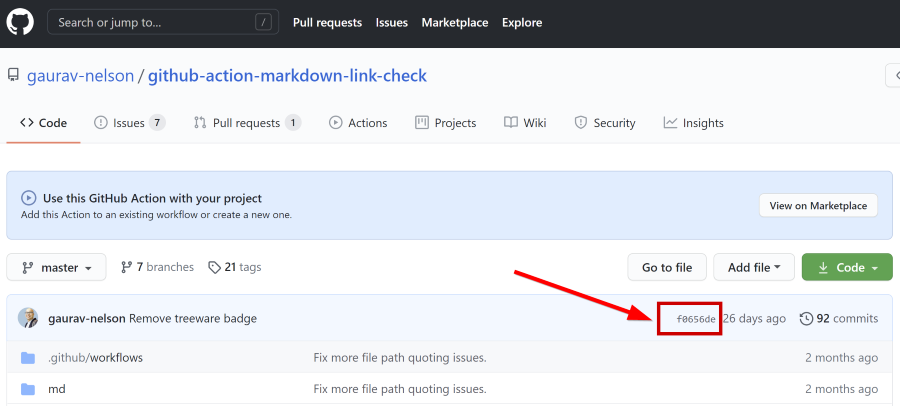

Safely pinning version by using the commit SHA

The best practice for pinning Action to the version you have reviewed, is by pinning it using the commit SHA: this value is created for each commit and is immutable: meaning that this value cannot be changed without changing the code and that any change to the code will generate a new commit SHA.

Example pinning the commit SHA

uses: gaurav-nelson/github-Action-markdown-link-check@f0656de48f62c1777d073db4a5816eba1dcc1364

In the example you see a full length commit SHA that will run for this Action. You can find the commit SHA from the source repository by going to the commit itself with this link:

Note: don’t use the short 8 character SHA: this is much less secure and will be deprecated as of February the 15th, 2021 (announcement). Always use the full SHA.

Forking repositories

The best best practice is to completely limit your organization to only use Actions from an organization you control yourself and then fork all Actions to that organization.

I recommend creating a specific organization that only has Actions repositories in them. That way I have a central location to manage all my Actions and I can limit the Actions that are allowed in any other organization I have.

Benefits of forking

An overview of the benefits of forking the Actions repositories:

- This gives you full control over the Actions you or your organization can use.

- You have a copy of the Action in case something happens with the maintainer or the repo of the Action (this should not be underestimated).

- You can review the Action’s code before you start using it in production (meaning your own workflows).

- You know for sure that the source code of the Action does not change between your own runs.

- You have full control over updates and when to review and incorporate them or not.

Don’t block DevOps teams

Keep in mind that only allowing Actions from your own organization will possibly block your DevOps teams from finding, testing and then incorporating new Actions in their daily work.

Follow the DevOps culture and empower teams to review new Actions and have a process to incorporate the new Actions in their normal workflows. This also allows them to take up ownership of the Action by reviewing the Actions source code before forking them to your Action’s organization.

To unblock them I recommend documenting the process and having a separate organization where they are free to test new Actions. Fork the Action repository there first, test them out and after diligently vetting the Action, fork them again into the production organization allowed in your normal workflows.

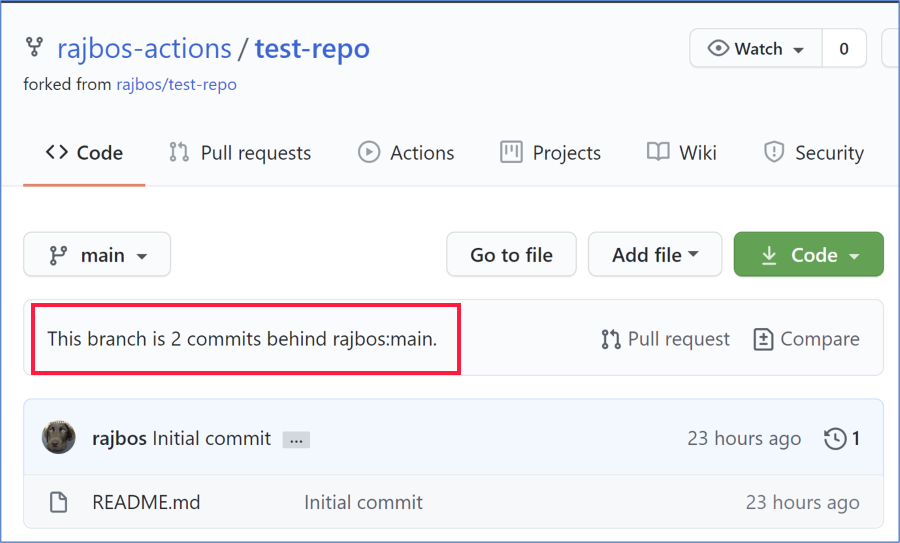

Keeping your forks up to date

If you are following the best best practice of forking the Actions you want to use, the you find another problem: how do you keep your forked repositories up to date? You can be on the lookout in the GitHub user interface for messages that your fork is a number of commits behind the parent repository, but when (if ever) will you come to that specific page?

Looking around I could not find a great way of keeping all Actions in your organization up to date AND giving you an option to review the incoming changes before you start using them, so I created my own 😁.

Keeping your forked (GitHub Actions) repositories up to date

I wanted a process that would update my forked repositories with these requirements:

- work for all forked repositories in my organization (so not just for one repo at a time)

- allow me to review the incoming changes

- update the forked repository with minimal manual intervention

- enable others to use this method as easy as possible

For this purpose I created this repository: github.com/rajbos/github-fork-updater. The information to start using it can be found in the readme and I will list them here as well:

- Fork the repo into your Actions organization.

- Enable issues (these are off by default for forks)

- Enable the workflows in the fork and enable the schedule on the

check-workflow(off for security reasons) - Trigger the

check-workflowmanually to get going (or wait for the schedule to be triggered, which is on workdays at 07:00) - Check any new issues being created

- Add a secret to the forked repository with the name

PAT_GITHUBand the rights to push changes to the repositories in your organization - Review the incoming changes for the fork you want to update

- Label the issue with

update-fork - Wait for the magic to happen

- Your fork is updated

- The issue is closed

- Sit back and wait for new notifications the next time the fork is out of date

You can also watch the demo video I created here:

Summary

This will make your life a lot easier. The default GitHub notification methods are used to notify you of new issues. All issues are always in the GitHub Fork Updater repository, instead of all over the place. And you can choose when to review the incoming changes and have an easy way to update the fork.