GitHub Actions & Security: Best practices - Private Runners

In this post I want to look into Private Runners for your GitHub Workflows and show you some best practices for them. GitHub Workflows can run on either a GitHub Hosted runner or on your own private runner. For the private runner you can install it on a machine of your choice and you maintain everything on that machine: the tools that you pre-install, the network stack the runner has access too and any storage it is using during its runs.

This post is part of a series on best practices for using GitHub Actions in a secure way. You can find the other posts here:

Photo by Sherise VD on Unsplash

Why use a private runner?

Some organizations have a policy that their builds (or deploys) always need to run in their own (hosted) datacenter. Another reason might be that you need to use some licensed software that you can run only on your own environment. Or maybe you need a GPU setup in your workflow (those aren’t available from GitHub Hosted Runners as far as I know).

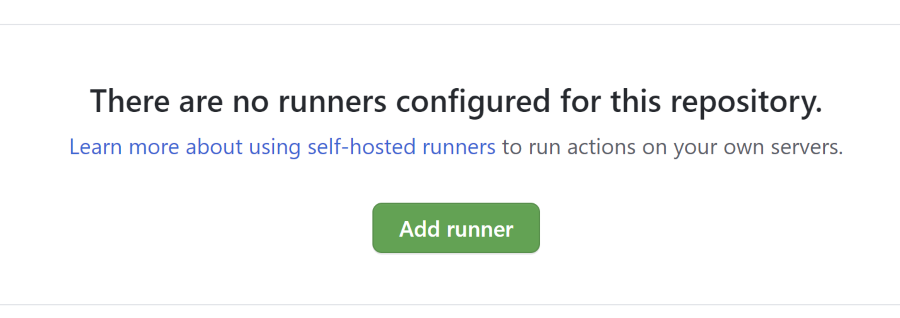

The runner itself is open source so you can look at the way it works and contribute updates to it. Installation is made very easy: you can go to your repository or organization or enterprise. Go to Settings –> Actions and at the bottom you can find a button to add a new runner.

If you add the runner at the organization level, it will be available to all repositories in that organization. If you add the runner at the enterprise level, it will be available to all repositories in all organizations in that enterprise.

Installation consists of executing these steps:

- Download the latest zipped version of the runner at https://github.com/actions/runner/releases

- Unzip it

- Run the config.cmd script with the url of the level to add the runner and a specific token (note you can also get this token trough the GitHub API). The token will be valid for 1 hour

- Start the runner

The runner will run with the privileges you provided during installation and will start a long polling outgoing connection over HTTPS to GitHub. It’s an outgoing connection for safety reasons (e.g. corporate firewalls) and goes out over HTTPS to make it as secure as possible. The runner will periodically ask GitHub (I think every minute) if there is work to do, and if not, back off for another minute.

Best practices in this post:

- Limit the access of your private runner

- Do not use a runner for more than one repository (on an persistent runner)

- Never use a private runner for your public repositories

If you want to learn more about hardening your runner environments, you can read the GitHub documentation here.

Limit the access of your private runner

Limit the access of the private runner to an absolute minimum. Think of all the things the processes the runner itself or the actions it will run for your have access to. Never install it with network admin or root rights. Give it just enough rights to only do what it was meant to do.

Does the runner really need to have access to your database cluster? If not, limit the network access for it (segment the network for example).

Does the runner really need access to your file share? What could it do with all those files? What if an action scans the share and start sending the interesting bits to an external server? What if the action executes your code, downloads a third party dependency that has been compromised and that starts to do something on your environment?

What happens if the action breaks the runner sandbox? Could it elevate itself to a more privileged account?

Best practice: give the runner the absolute least amount of access it needs to the machine it runs on.

Do not use a persistent runner for more than one repository

This best practice comes from the same practice as before and mostly comes from the methods used in supply chain attacks like for example the recent Solorigate attack. Both the action that is being executed and the third party dependencies it uses (NPM or NuGet packages or all the layers in the Docker image it uses) can store things on the runner machine. Even the runner itself could store these things, although a compromise of the runner is less likely, it could still happen (we’re all humans after all). Context here matters: this is not so relevant for what we call an ephemeral runner: a runner that only exists for the duration of one job (not workflow!). Having data persisted on an ephemeral runner is not possible, since the runner will be deleted afterwards.

This topic is of course super important for persistent runners: think of a Virtual Machine that is constantly running.

What if a first run downloads a compromised package and stores that in your local package cache? A second run that needs that package, finds it in the package cache and uses that version instead of retrieving the correct one? As in the Solorigate attack, only 1 assembly was overwritten as a starting point of the compromise.

This problem could even be enlarged by using the same runner for multiple repositories: Package cache poisoning in one repository could be subsequently be used by all other workflows that are executed on the same runner.

Even worse: installing multiple runners on the same machine in an effort to enable more efficient use of the available resources on the machine: what if they all use the same package cache. NuGet uses a centrally stored cache on the machine level for example…

So as a best practice: if you really need a runner, create at least a new runner on a new machine for each repo and give it the minimum rights it needs to do its work.

An even better option is to create a new runner for each run. For example use an Action that creates a new runner just for that specific run, or host your runner on AWS Fargate or even setup auto-scaling yourself.

Note: the options above all use AWS for hosting. I haven’t seen any examples for this setup on Azure yet. If you have an Azure Example, let me know: I will add it to the list above.

Never use a private runner for your public repositories

Also mentioned in the guidance from GitHub is that you should not use private runners for public repositories. Depending on your setup, your workflows will be triggered by new commits being pushed to the repository, or by an incoming pull request.

What if someone with ill-contempt forks your repository, adds code or a dependency that will compromise your setup (or even the workflow itself) and create a new Pull Request on your repository? The workflow will be triggered (hey, they can even add the trigger for you!) and the malicious setup will run on your machine with all the access the runner has. This is considered very dangerous for obvious reasons.