Azure DevOps Marketplace News - Or Imposter Syndrome for developers?

I’ve been developing software for over 16 years now and every now and then I come across someone who thinks developers do something magic that they can never learn to do. Maybe they are even afraid to ask us something because they don’t understand something. As a consultant my role has often meant that I could take the time and explain to someone more functional oriented the reasoning behind some decisions a developer could make.

Photo by Clem Onojeghuo on Unsplash

So this post is meant as an example battling against imposter syndrome and to openly document the development process and some key decisions along the way and give an insight about the stuff I need to look up (hint: it is a lot!).

The git repository with the source for the tool is open source and can be found on Github.

All in all I have spend around 6 hours in an editor (measured with the WakaTime extension) over the course of 2 weeks to get a working twitter account that checks something every three hours and tweets about it if needed.

Reason this project exists

The reason I started with this project is that I always wondered if there could be a way to stay up to date on Azure DevOps extensions on the Marketplace: there are many extensions available in it and if you don’t check the marketplace regularly, you can easily miss some gems. Of course, when you encounter a specific problem, you will probably find the extensions when you need them, but I thought this was a fun thing to do.

Searching around did seemed to prove there isn’t a good way to stay up to date on the extensions: there is no RSS feed, Twitter bot, or any other option than to regularly check the “Most recent” feed. Since I still am a developer, I thought I could probably make something myself and that this should be a fun thing to do that should not cost to much time to make!

Functional requirements

My own functional requirements where quite easy:

- Check the marketplace data periodically for changes.

- Tweet about them on a new account when found.

Seems straightforward and not that hard!

Research

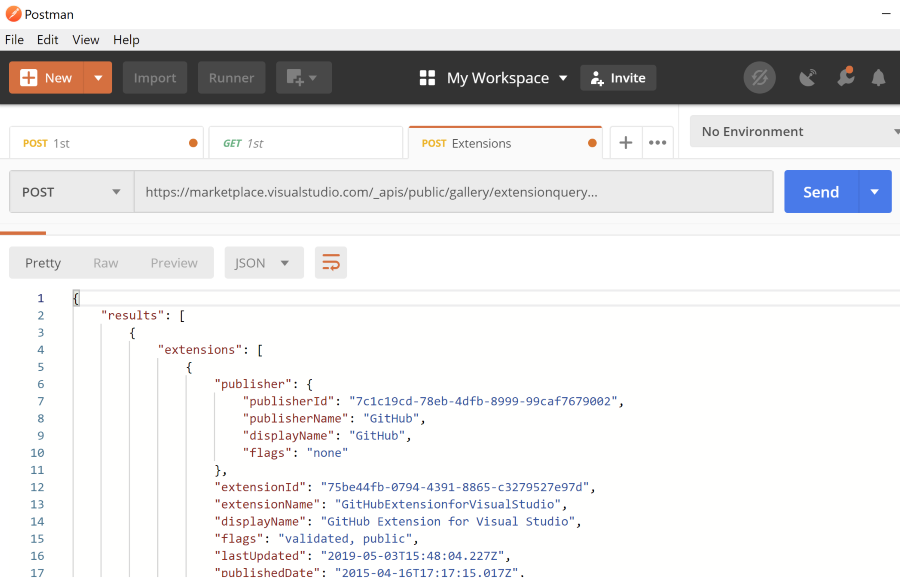

To check if this is even possible with the API, I opened up the developer tools in Chrome and checked the calls that the marketplace page makes to the back-end. After finding the call that seemed to response with actual JSON data that listed all the extensions, I checked that I could make the same call in Postman and actually get some results: that way I knew that I didn’t need to login to an API or send in some magic cookies or something.

Seeing results in Postman meant that this whole idea is feasible at all an convinced me to get started. I needed a tool around the calls, somewhere to store the current data, diff any changes and then tweet about new or updated extensions. So just a couple of components 😄.

Starting point

I didn’t want to start exploring fun new technologies to get all the necessary steps working: I just wanted to be notified when there was a new extension available! Therefor I decided to play my strengths and stick with what I have been using for more than five years:

- Git repository

- C# with .NET core

- Azure DevOps

First real commit

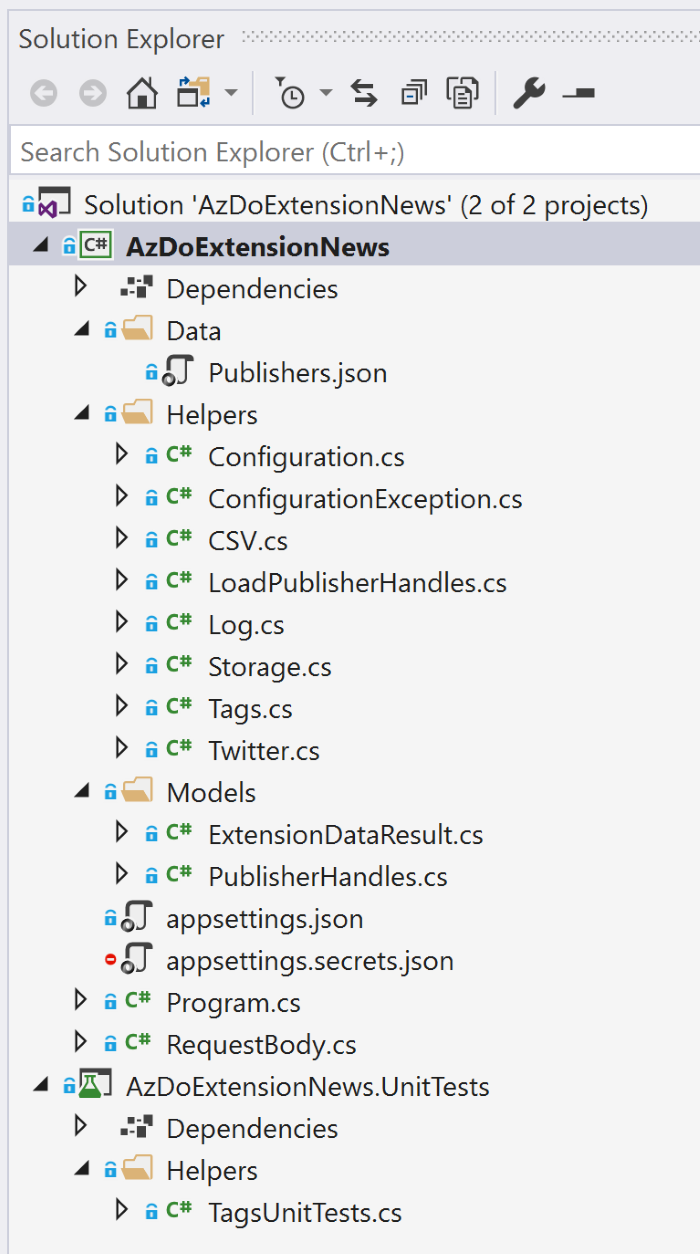

Starting in Visual Studio with File –> New –> .NET Core Console Application after creating a new Git repo I quickly created an outline to load the information from the API.

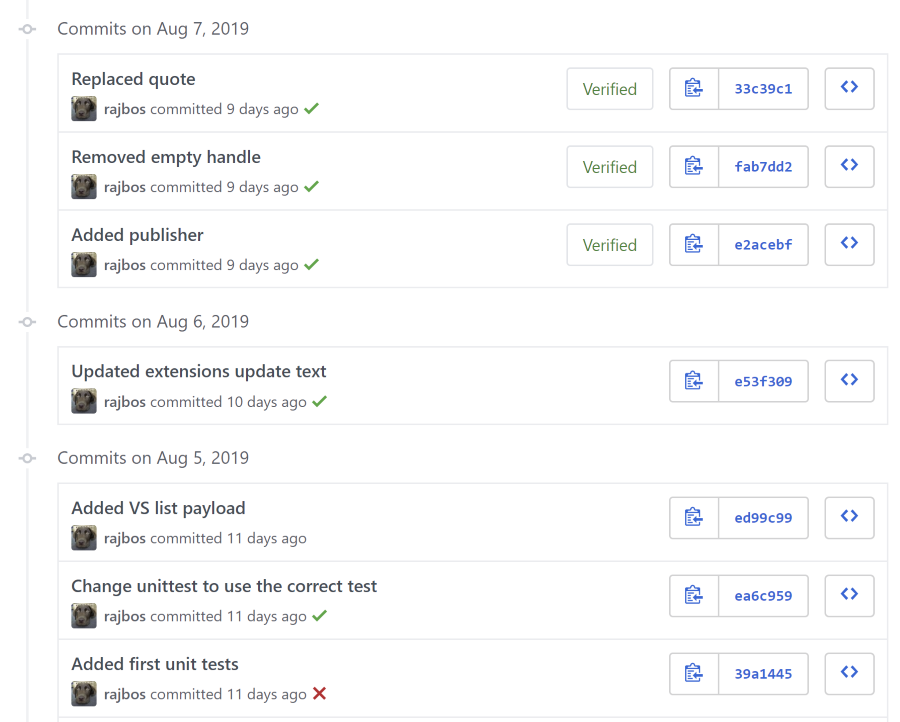

In the first commit you can see the thinking process and coding style that I use when building a MVP (minimal viable product).

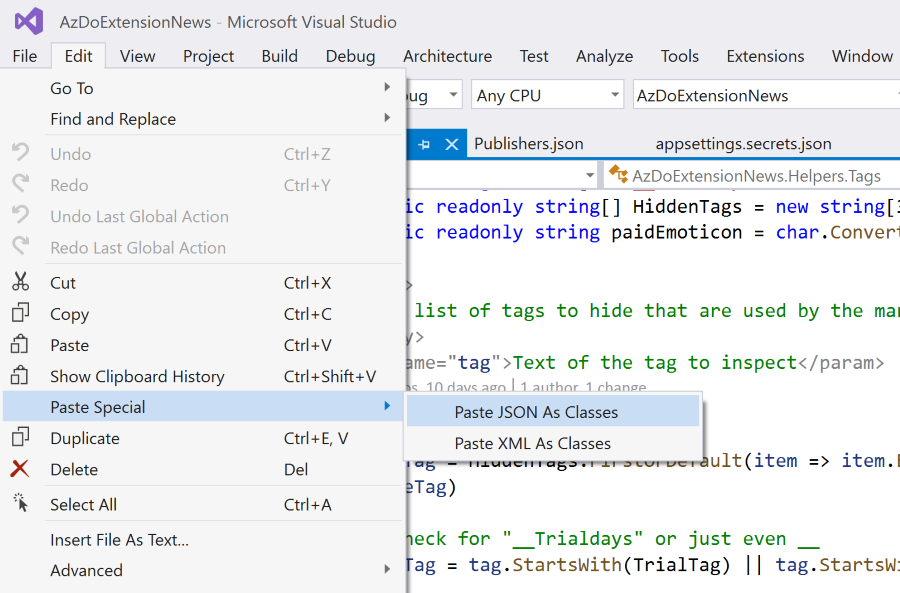

Everything is still in the Program class with a lot of to-do’s in it. Some data classes like ExtensionDataResult.cs are separated and just filled with the awesome Visual Studio feature “Paste JSON as Classes”.

At this point I was mostly trying to get the download working and store the results in a list so I could easily start a diff method next.

I haven’t found it easy to do any TDD around my code, especially not at first, and because I was the only developer I skipped all those best practices 😁. Seeing this as a fun side project supported that decision. My head still seems to work in a different way and I like to see the results as soon as possible.

Searching for code

To give a feel for the amount of searching around I did to actually create a tool around my own needs:

- Working with HttpClient to send calls to the Marketplace API: looked it up in a different project.

- Serializing the result with Newtonsoft.Json: googled it.

- Sending a tweet through the Twitter API: found an example on Stack Overflow

- Setting up a developer account on Twitter so that I can tweet: googled it.

- Exporting a list to CSV: googled it.

- Storing the data in an Azure Storage Account using blobs: looked it up in a different project.

Flow

After getting the JSON results and de-serializing them, I wanted to see what overall information was in the dataset, if there where any duplicates and other stuff that stood out. One of the quickest ways to do this for me is in good old Excel: just export a CSV and load it in, create a pivot table on it and go to town. From that I learned that I did need to deduplicate the list and that there are tags that could mean that the extension was pushed to the marketplace but was not made public yet. Good checks to add to the application.

Running locally

This is still a console application that I run in debug mode to see if everything works. Next step was storing the data to disk, so I could create a method to diff the lists between the previous check and the current one. When I found changes in the next day (remember that this took two weeks to complete?), I searched around for some code on how to create tweets from the changes. I found an example on Stack Overflow that looked okay and just worked, so I’ve included that in a separate class. I haven’t even added a real secret store yet: I am just running it from appSettings.json with an optional load of appSettings.secrets.json! Yes, quick and dirty 😛. I did make sure to add that file to the .gitignore before committing, so that is fine for my single developer use case.

I think I ran with this setup for at least a week, running it multiple times a day, right from Visual Studio. I added logging on any exceptions that occurred, added extra information to the tweets, like the name of the publisher, using the tags as Twitter hashtags, etc.

After running for a couple of days I got some feedback about some of the tags that seemed to be tags that the marketplace website uses to determine for instance if the extension is paid or if it has a trial period attached to it. That has been added in as well.

I also thought it would be nice to add the publishers to the tweet themselves if I could find their Twitter accounts. The first publishers have been added to a hard-coded list.

See how gradually this has progressed? Everything has been added when I actually had a need, and refactored into separate classes when those parts felt ready.

Unit tests

Only recently I added my first unit test to the project, because I wanted to test if the Azure DevOps publish tags would work correctly: that is a comma separated string in the JSON object and I created some tests to make sure those would work.

Automated runs

The next step was to run the tool somewhere in an automated fashion. I could do something fancy and go to a serverless solution, but in the current iteration had enough value in it for myself, so I just need it to run somewhere. I could have just added a local Windows Task that ran the tool on an interval or something, but that was not good enough: I wanted to run every couple of hours, even when my laptop was not running. I also did not want to add all kinds of exception handling in the case the tool was running and my WiFi lost its connection or the laptop was being shutdown. Basically I needed a scheduler that could run my .NET Core tool.

Preparation

Before I could run the tool on a different machine, I needed to make sure that the data file that I was saving locally on each run, would not interfere with a local file for the Azure DevOps Agent. Time to start storing that file in an Azure Storage Account as a blob! Only now I’ve added the code to do this. If you check the code, you can find that all I’ve changed is downloading and uploading the file from blob storage to a local copy. The rest of the code has not been changed, because it worked. No need to go to an in-memory solution without writing the file to disk, the current code works and speed is not an issue if I run once every three hours.

Azure Pipelines

As a consultant I currently live and breathe Azure DevOps on a daily basis, so this tool is my big scheduling hammer: I don’t need any other fancy stuff, just run it every three hours and let me know if something happens. I have an MSDN account that I can use for these test projects and as Azure DevOps provides unlimited pipeline minutes on open source projects, this fits perfectly.

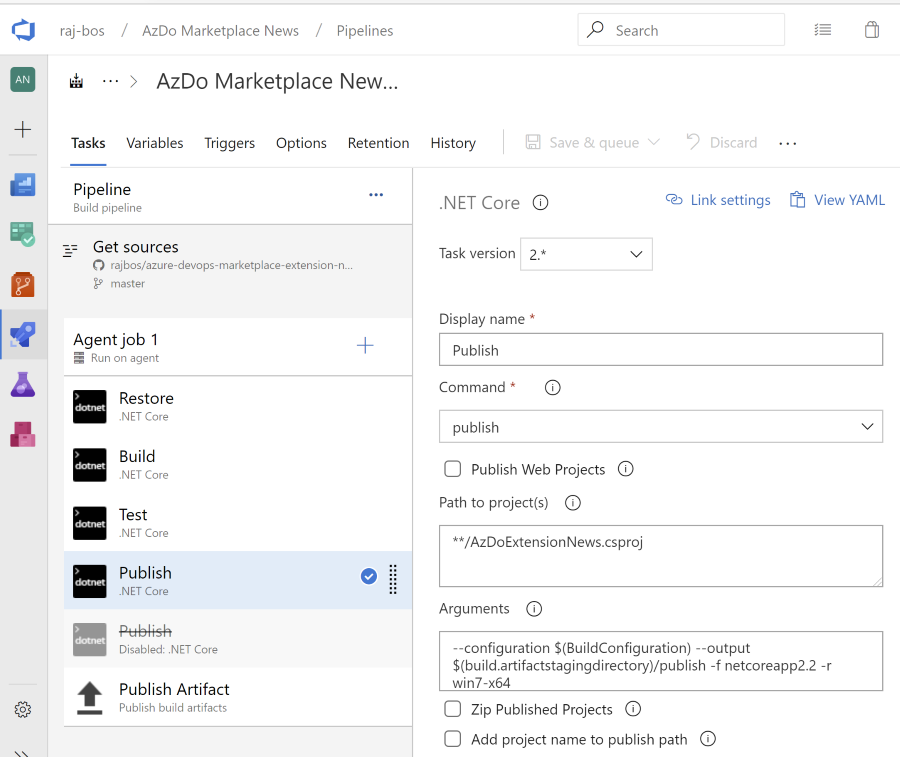

Building the solution

The first step is building the solution. I could run it from the build but that seems like overkill: the solution should not change that much that often (after the first few iterations) and adding a release for something in .NET should not be that much work.

I started with the default ASP.NET core web template. That uses the flag Publish Web Projects to publish a zip file with a WebDeploy package in it. Since we cannot use that I changed the publish step.

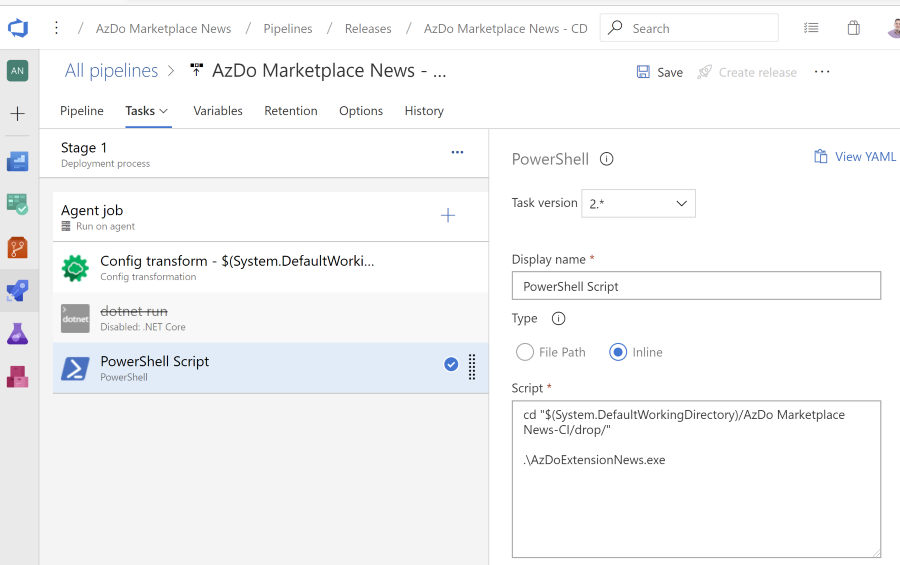

Later on I found out that the release cannot handle the normal .NET core DLL that is generated instead of a .NET executable: the .NET core tasks do not support executing the dll with the .NET run command: it wants the .NET core project folder to first build and then run the solution. I had to work around it by publishing a full .NET core app targeting the Windows platform. That way I have an executable that I can trigger with a PowerShell task.

Release or run pipeline

The release just consists of extracting the build artefact, overwriting the application settings with an Azure DevOps Extension.

Full circle

I started out with a Git repo, pushed that to GitHub, build and run in Azure DevOps and then report the status of the build and release through badges in Azure DevOps and included those in the readme of the repository:

| Step | Latest execution |

|---|---|

| Build | |

| Release/Run status |

By the way, I am using Azure Pipelines from the GitHub marketplace to run the CI/CD triggers for the project.

For the scheduling part I am using a scheduled trigger that will run the release definition every three hours. Somewhat irksome to add so many (no cron notation), but if it works….

Conclusion

I hope this gives an insight to the development process to someone that is curious and maybe helps to lower some of the imposter syndrome that some developers seem to have (myself included!). With a good mindset you can figure things out or just reach out and ask for help. With that, you can get anything done!